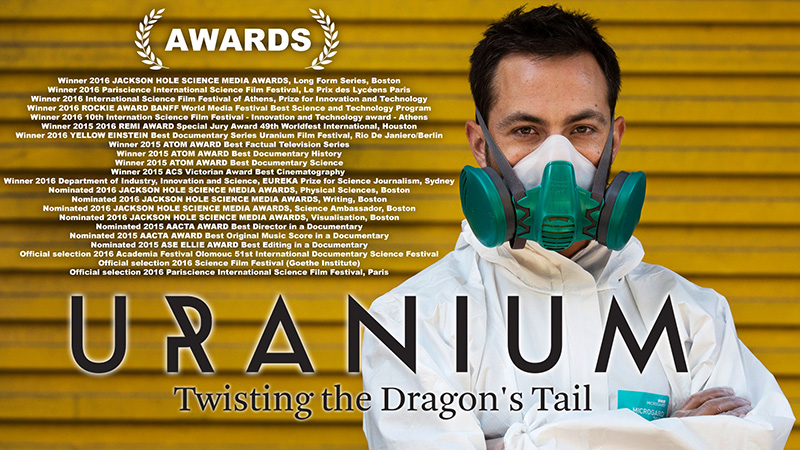

Uranium: Twisting the Dragon's Tail

Writer Director — 3x1 hour / 2x1 hour Television Feature

Legends say there’s a world beneath this one where a dragon lies sleeping. They say be careful how you wake the dragon.

Pick of the week, highlight of the day — Los Angles Times, Boston Globe, Newsday, USA Today, Washington Post, San Francisco Cronicle.

The year 2015 marks the seventieth anniversary of the most profound change in the history of human enterprise on planet Earth: the unleashing of the elemental force within uranium, the explosion of the atomic bomb, the unleashing of the dragon.

Come on an epic journey through nine countries and over a century of stories with physicist Dr Derek Muller to discover the untold story of the most wondrous and terrifying rock on Earth.

‘I’ve never felt so nervous while watching a PBS documentary before… I had to pause the video to make some tea just to calm down.’ — Michigan Daily

‘The mix of science, politics and pop culture makes for a tale that’s by turns terrifying and utopian, but never less than fascinating.’ — Sunday Best, Karl Quinn, Sydney Morning Herald

Episode 1 — The rock that became a bomb

At the turn of the 20th century uranium is virtually unknown and basically worthless. Dr Derek Muller embarks on an adventure to reveal how, in just a single generation, uranium transforms into the most valuable and terrifying rock on Earth.The discoveries of scientists such as Marie Curie, Ernest Rutherford and Albert Einstein unlock the secrets of the uranium atom, and allow us to peer into the very nature of the universe. Then one clear morning above the city of Hiroshima, uranium unleashes a terrifying power and changes the world forever.

‘Get on it, it's one of the best science documentaries we’ve seen in a long time.’ — Science Alert

‘…an enlightening, engaging film, with the cosmic history and chemistry of uranium well-explained. Muller's excitement over what's amazing can seem at odds with what is also horrifying… But you will see him scared, too.’ — Robert Lloyd, Critics TV Picks Los Angeles Times

Episode 2 — The rock that changed the world

In Northern Australia the indigenous people have ancient stories for the place where the uranium is found. They say a great creation spirit sleeps underground, and disturbing this spirit will unleash disaster. Dr Derek Muller takes us on a remarkable journey to see how from the ashes of Hiroshima, uranium promised a new age. The same power that destroyed the city will be harnessed to generate unprecedented amounts of energy. We had woken the nuclear dragon, and disaster was waiting.

TV Highlights - 'Physicist Derek Muller breaks down uranium’s history and secrets in “Uranium: Twisting the Dragon’s Tail”’ — Lauren McEwan, The Washington Post

‘…brilliantly written and directed by Wain Fimeri… presented with panache by Derek Muller… undoubtedly one of the most talented science communicators of our time… This is one not to be missed.’ — Bill Condie, Cosmos Magazine

Episode 3 — The rock in our future

Uranium saves lives, treats cancer and brings hope to millions. Uranium was also a promise of clean limitless power. In a remarkable and haunting journey, Dr Derek Muller takes us to Chernobyl and Fukushima, where uranium became a nightmare. In our energy-hungry, increasingly warming world, uranium both tempts with unbelievable power and threatens all life on earth. Destroyer and saviour, dream and nightmare: the extraordinary paradox of uranium.

‘The three-part documentary series gives the controversial element rock-star treatment… Dr Muller’s journey also delves into the ancient Aboriginal Dreamtime and the fantastical nature of the element, resulting in a colourful and engaging journey about an extraordinary rock.’ — Sunday Pick, Tiffany Fox, West Australian.

Pick of the week. ‘Aussie-born YouTube science guy Derek Muller has a huge thing for uranium’ — Anna Brain, Daily Telegraph

‘ “Uranium” is lively, engaging and informative… a terrific - and slightly loopy - Muller tour of a single element. He's straight out of the school of Carl Sagan hosting - smart, lively, demonstrative, quirky.’ — Verne Gay, Newsday

HOT LIST! ‘…you shouldn’t miss… Pick of the day! Uranium, Twisting the Dragon’s Tail.’ — The Age Melbourne

WATCH THE TRAILER

Director's Statement

During filming for the documentary series, ‘Uranium Twisting the Dragon’s Tail, I kept a journal when I could. This is an extract. From the town of Chernobyl.

42 seconds was all it took for an ordinary early morning at the Chernobyl nuclear power station to turn into a terrifying day. Some of the safety systems at the plant had been disabled well before that morning when some technician at reactor number 4 performed a routine test and some gewgaw closed when it should have opened, or maybe it was the reverse, but it was definitely a combination of human error and crap Soviet technology and all I can imagine now, is the quick upturn of the technician’s eyes to the gauges. They were glowing. The demon that lives in the core had broken out.

A great invisible radioactive dragon rose into the darkness on shimmering wings, and flew the breadth of Europe. The Soviets displayed a genius for public relations and didn’t tell anyone. It was the Swedes, 1500 kilometres away in Sweden who twigged first. They were getting high radiation readings and it didn’t make any sense. They had no leaks, no breaches in any of their nuclear facilities.

Then, when the Soviets couldn’t keep it secret any longer, they reluctantly told the world and what they described, was the worst nuclear accident in history. Far, far worse than Fukushima.

The Soviets declared a 2600 square kilometre zone about the crippled reactor. They evacuated everybody from this zone and the landscape become empty. Forbidden. They called it the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

These days, about seven thousand people live in the small town of Chernobyl. They are almost all employed in maintaining the Exclusion Zone. Engineers, scientists, and construction workers. Most people left Chernobyl because of the accident, but not because of the radiation.

They left because of the economy. The crippled nuclear reactor is some 15 kilometres to the north of the town and the morning when Reactor number 4 blew, the wind was southerly. The great fetid cloud of radioactive Strontium, Caesium and Iodine blew to the north, all the way to Sweden, and Chernobyl escaped relatively unscathed but the misting drift of radioactive poison that settled like dust over the land did it in for the town. The evacuation and subsequent Exclusion Zone meant all the work disappeared too. So lucky, innocent Chernobyl received a dreadful reputation and a kick in guts all in one morning.

Chernobyl has one hotel. The walls are made of paper and pie crust. There's isn't a true line or square corner anywhere. Walking the corridor gives you vertigo.

The door opens into the hat rack. It’s a wonky gimcrack world where nobody really gives a shit. Almost all the men wear military camouflage clothing. It's got nothing to do with the war in Ukraine though no doubt that hasn't discouraged the fashion. No they dress like this all the time. The dining room looks like a convention of jungle hell leisure suit enthusiasts. They drink neat vodka and eat sliced, smoked meat. It's a diet of acetone and lard and it doesn't help. The waitress plunks the plates down hard.

You must have a permit to travel into the Exclusion Zone and it isn’t easy to obtain. We had one because we are a film crew. Most people take an organized tour because in 2011 parts of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone were declared a tourist attraction and today, the main business of Chernobyl and it’s gruff men and cranky waitress, is catering to tourists. The numbers are down these days. ‘It’s the war,’ they shrug. Annoyed, because the war is 800 kilometres away and they have the best tourist attraction in the world if you like radioactive exclusion zones.

We have been making energy by boiling water for about three hundred years. Boiling water makes steam. Steam powers machines. You can boil water by burning wood or coal or oil or gas or you can boil water by splitting uranium atoms in a nuclear reactor. Splitting uranium atoms releases heat that makes steam that turns a generator and that generates electricity. It’s simple.

A nuclear power plant is just a tremendously complex way to boil water. It’s also efficient. There’s more energy in a uranium fuel pellet the size of a pencil eraser, than there is in a ton of coal. But there’s a downside.

The western part of Ukraine is magnificent country. In autumn, everything that isn’t green is rust red or yellow like dappled sunlight. The roads are empty. And then a checkpoint looms. A small guard hut and a red and white boom gate across the road. The guards wave us to a stop and check our papers and grunt and lift the boom and we are through, into the Exclusion Zone.

These days it’s called the Polesky State Radiation Reserve which sounds nicer, and soon you are driving past the number 4 reactor itself. It’s a mess. A big chimney and a profusion of pipes. It looks exactly like a big ruined factory.

When the nuclear reactor blew, it scattered the tiny fragments of split uranium atoms across the landscape where they settled like dust, but it was a capricious dusting dependent upon the wind, so some places barely register on our Geiger counters and some places, set off our alarms. Even travelling inside the car.

A couple of kilometres north of the reactor is the city of Pripyat. It was built to house the workers and their families who serviced the Chernobyl power plant. Pripyat was evacuated the day after the accident. 50 thousand people were told to pack a toothbrush and board a fleet of busses for an evacuation they were told would be temporary.

So 50 thousand people stopped what they were doing and left. They left washing on the line and plates of food on the table and the lids of pianos open, and they have never returned.

Today the warm forest slowly claims Pripyat. Trees grow through the streets. Thrust themselves through the pavements. Vines snake through the children’s playground. A Ferris wheel stark against the sky, the yellow gondolas swing gently and squeal softly. It’s eerie. It's the world after everybody has gone. This is what the world looks like without people.

We found a kindergarten. Silent toys and little empty bunk beds and as we move through the rooms, our Geiger counters click and the leaves from the trees that have grown right to the windows scratch gently on the glass. Dusty rooms. A tangle of dropped school books. Beeping radiation monitors. Sighs, and a gentle billow of curtains.

When the reactor blew that early morning in 1986 the roof of the building caught fire so the first responders to the accident were the Pripyat firemen. They had no idea they were charging into lethal radiation. When they did, they kept charging. Astonishing courage. They put out the fire and by that afternoon, they began to die.

They took the dying firemen to Pripyat hospital and when the staff there realized how radioactive the firemen’s clothing was, they threw it down in the basement in a big pile. Then next day, everyone was evacuated from Pripyat.

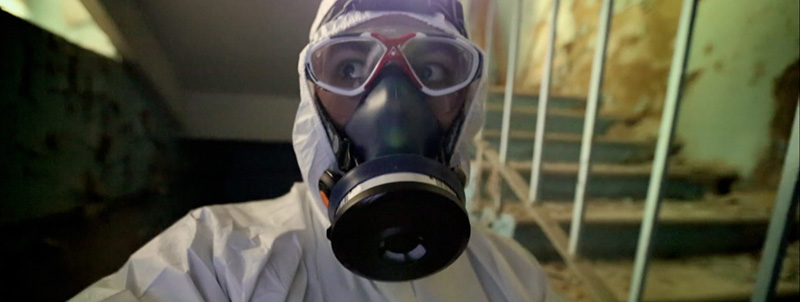

We found the doors to the emergency room of the Pripyat hospital through the trees very like the children found Narnia through the wardrobe. We looked at the doors and we breathed deeply and we suited up with gear we had brought, respirators, masks and suits. Latex gloves and booties. This will protect us against some of the radiation but not the stuff that travels at the speed of light straight through you like sunlight goes through a window. We entered the hospital with flashlights and we descended carefully down the stairs and into the darkness. We inched carefully along the corridors. The walls are painted green, peeling like flaked skin they loom out of the darkness and as we progress, I’m holding my Geiger counter before me as a vampire hunter holds aloft a crucifix. The further we go the beeping increases in intensity and the deeper we go into the darkness the beeping begins to shrill faster. And faster.

On the floor ahead, in a cone of light, what we have come to see. A boot on the floor. A tunic. A helmet. The firemen's clothing is still here. All covered in the radioactive dust from the terror and passion of that morning thirty years ago. Our Geiger counters shrieked. Then they screamed and read 'overload' and shut down. The radiation is still too high. Four minutes down here is enough.

We had to leave. But we had seen the clothing of the firemen of Chernobyl.